"Still belief persisted in the magic of credit to achieve all economic objectives. ... This pathetic and muddled belief in the power of credit to cure all economic ills is perennial in New Zealand ...

"It was a factor in the Labour Party's seeping victory in 1935 ... It was potent throughout the Labour Party's tenure of office and never more potent than in the post-war years when it was least applicable."

~ JB Condliffe writing after the WWII) of the New Zealander's enthusiasm for cheap money, in his 1959 book The Welfare State in New Zealand

Friday, 28 November 2025

"This pathetic and muddled belief in the power of credit to cure all economic ills is perennial in New Zealand"

Tuesday, 25 November 2025

Were Maori environmentalists? [updated]

A friend who wrote a thesis several years ago on common law solutions to environmentalism asked me this question a few weeks ago, and I've only recently got around to answering (I've paraphrased the question just a little):

Q: How did Maori activists [he asks] attain the apparent status they now possess in the environmental movement? In other words, why do NZ environmentalists bow to Maori prejudices? When I wrote my thesis this absurdity was not evident as it is now. Please can anybody shed some light on this?So here's my rather belated answer.

On the facts of pre-European Maori environmental stewardship , the best I've read is a shortish piece by M.S. McGlone et al: 'An Ecological Approach to the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand' published in The Origins of the First New Zealanders [Auckland University Press, 1994.] Unfortunately, it's not online (although I do quote from it briefly in this article), but it does rather give the lie to the idea of Maori as sound environmental stewards.

On the facts of pre-European Maori environmental stewardship , the best I've read is a shortish piece by M.S. McGlone et al: 'An Ecological Approach to the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand' published in The Origins of the First New Zealanders [Auckland University Press, 1994.] Unfortunately, it's not online (although I do quote from it briefly in this article), but it does rather give the lie to the idea of Maori as sound environmental stewards.Take bird life for example.

"James et al estimate that untouched Oceania may have had more than 9000 bird species -- more than the total of surviving species on Earth today. Most of this incredibly rich fauna was eliminated by the direct or indirect effect of [pre-European] settlement... The amount of accessible fat and protein per square kilometre on a Pacific island may have been unequalled anywhere in the world...

Direct evidence exists for this superabundance of bird and marine resources on unexploited islands... In the initial settlement period [of New Zealand], the early abundance of bird bone must have represented a truly incredible exploitation rate... [Yet] NZ midden evidence shows that the consistent exploitation of birds in the late prehisoric results in few bird-bone remains...

The extinction of birds other than moa and of reptiles, and the shrinking of the range of many other species are well-attested (Cassels 1984)... the absence of these species in natural deposits such as caves, swamps and sand dunes after about 1,000 years ago strongly suggests early and vigorous depletion...

In summary: the birds were being killed and eaten in great numbers, in complete disregard it seems of any long-term consequences.

In summary: the birds were being killed and eaten in great numbers, in complete disregard it seems of any long-term consequences.The case is the same for New Zealand flora. Slash and burn agriculture "rapidly destroyed much of the forest cover... By 600 years [Before Present] many animals had been driven to extinction or close to it, and very large areas of country, even in remote inland South Island valleys, were being burnt regularly... A degree of burning may been beneficial, for a [short] time at least."

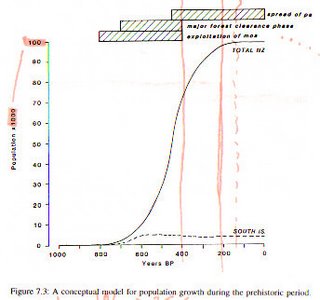

However, over the longer term: "Extensive burning of inland valleys and ridges offered no obvious advantages in terms of food production..." The result of indigenous environmental stewardship over the longer term? Population grew rapidly in the North Island of NZ from 800 years BP, before slowing down about 400 years BP (following the major forest clearance phase) and plateauing about 200 years BP at about 100,000 when resources began diminishing (see graph at right).

However, over the longer term: "Extensive burning of inland valleys and ridges offered no obvious advantages in terms of food production..." The result of indigenous environmental stewardship over the longer term? Population grew rapidly in the North Island of NZ from 800 years BP, before slowing down about 400 years BP (following the major forest clearance phase) and plateauing about 200 years BP at about 100,000 when resources began diminishing (see graph at right).After the initial settlement phase, New Zealand moved directly into a subsistence mode which characterised other island populations only during famine or when pushed into highly marginal lands... By the end of the prehistoric period New Zealand was no longer resource-rich, and the very scarcity of resources and reliance on hard-won wild foods had created a situation from which no larger political entities could easily arise.So the idea of Maori as sound environmental stewards is not supported by the archaeological evidence. As 'sustainable' environmentalists they just weren't. So how to explain then the apparent status they now possess in the environmental movement? The reason is more widespread than is contained in environmentalism alone.

I think there's perhaps three legs in answer to the question, all related.

1. The Noble Savage

As Roger Sandall amongst others has noted, "A 'savage,'' untouched by civilization, would be akin to an animal, and neither noble nor a good role model for a society. By viewing civilization as something that corrupts or taints a person's pure or natural state, 'new tribalists' are succumbing, like Rousseau, to the romantic idea that the natural state of a human being, without the moderating effect of civilization, is somehow better. To the critics this notion is easily refutable, either by comparing human quality of life before civilization, or as humorist P.J. O'Rourke pointed out, by considering the natural state of children."

In Sandall's view, [summarises Wikipedia] romantic primitivism places far too high a value on cultures that were often characterised by, among other aspects, limited human rights, religious intolerance, disease and poverty. Other negative aspects he discusses include domestic oppression (usually of women and children), violence, clan/tribal warfare, poor care of the environment and considerable restriction on artistic freedom of expression.'The Four Stages of Noble Savagery: The Moral Transiguration of the Tribal World' is the Appendix to Sandall's book, 'The Culture Cult,' and is highly readable on this question. He concludes by discussing the 'Disneyfication' of the 'Noble Savage':

Sentimentalism begets puerility. The ruthless scalpers of yesterday become Loving Persons. One-time ferocious fighters are discovered to be Artists at Heart. Hollywood becomes interested...

Combined with this a suffocating religiosity now descends on public discussion, enforced by priests and judges, journalists and teachers, poets and politicians, all of whom claim that native culture possesses a “spirituality” found nowhere else. Soon the primitive is elevated above the civilized. In the words of one observer in New Zealand it is said that the whites “have lost the appreciation for magic and the capacity for wonder” while white culture, besides being “out of step with nature. . . pollutes the environment and lacks a close tie with the land.”

Few are unkind enough to note that “the imagined ancestors with whom the Pacific is being repopulated”—Wise Ecologists, Mystical Sages, and Pacifist Saints—“are in many ways creations of Western imagination.”

Just like Pocohantas. Or Chief Seattle.

2. 'The National Question'

The second leg is specifically political, the idea that Lenin called 'The National Question' -- a specific strategy adopted by Marxist-Leninists to help destabilise a colonised country by use of the grievances, real or otherwise, of indigenous populations.

This movement came to attention in NZ in the late seventies (made most visible with the 'Treaty is a Fraud' movement), and you might say that reached its apogee under Neville Bolger's appeasing stewardship (when it suddenly transmogrified into an'Honour the Treaty' movement).

When mainstream Marxism collapsed following the collapse of the Berlin Wall -- and with it any claim that Marxist societies would ever be able to produce (or be good environmental stewards) -- rather than give up their authoritarianism, the custodians of 'The National Question' stampeded into local and overseas environmental movements. Consequently, the numbers of 'National Question' adherents and other fellow-travellers (the gullible type whom Lenin called Useful Idiots) who call themselves 'green' but are still red on the inside would seem to be quite large.

3. Multiculturalism

The third leg, related to and in some sense underpinning both, is the notion of 'multiculturalism' -- the idea that all cultures are equal (apart, that is, from the cultures of the west). 'Multi-culti is one of the many foolish notions of postmodernism, (encompassing both moral relativism and political correctness) that captured the academies in recent years.

Naturally when the least are made equal to the best, the least win out. If all cultures are asserted (without evidence) to be equal, then one is disarmed from finding evidence that would disprove such an assertion. To find and assert such evidence would, according to the multiculturalist, be 'racist.'

The consequence is this: If one is disarmed from judging a culture -- which is one of the goals of moral relativism -- then the worst cultures are left free from moral judgement, and moral judgement itself becomes bereft of any evidential-base: the only immorality to a multiculturalist is to challenge the assertions of multiculturalism. That too would be racist.

But as Thomas Sowell points out, you can judge cultures, and in fact if human life is our standard then morality demands that we should judge them.

Cultures [he insists] are not museum-pieces. They are the working machinery of everyday life. Unlike objects of aesthetic contemplation, working machinery is judged by how well it works, compared to the alternatives. The judgment that matters is not the judgment of observers and theorists, but the judgment implicit in millions of individual decisions to retain or abandon particular cultural practices, decisions made by those who personally benefit or who personally pay the price of inefficiency and obsolescence."

Anyway, on this last point you might want to have a good look at:

- My own Multiculturalism archives.

- Thomas Sowell's book Conquest and Cultures.

- George Reisman's superb pamphlet 'Education and the Racist Road to Barbarism,' which pretty much explains and explodes the process and the arguments behind multiculturalism.

- 'Multiculturalism: The New Racism,' a special issue of the Ayn Rand Institute's 'Impact' magazine.' [Cover story here]

- And for a background to how they get away with it philosophically, you might take a good look also at Stephen Hicks's superb book Explaining Postmodernism [free PDF here] - you can read a summary of the book's thesis here in an interview with Hicks.

REFERENCES CITED ABOVE IN McGLONE et al:

- Cassells, R., 1984: 'The role of prehistoric man in the faunal extinctions of New Zealand and other Pacific Islands,' in Martin et al Quaternary Extinctions, Uni of Arizona Press.

- James et al, 1987: 'Radiocarbon dates on bones of extinct birds from Hawaii,' Proceedings of the Nat. Academy of Sciences of the USA, 84.

- Leach, H.M., 1980: 'Incompatible land use patterns in Maori food production,' New Zealand Archaeological Ass. Newsletter, v.23.

UPDATE: Matua Kahurangi takes a look at a current example of non-kaitiakitanga where bureaucratic management, bad incentives and pisspoor efforts at conservation combine in the worst of all worlds ....

For years, the Ureweras have been celebrated as a showcase of iwi stewardship and environmental guardianship. But the reality is far bleaker. Tūhoe leadership is presiding over mismanagement, neglect, and a shocking lack of accountability, turning what should be a model of co-governance into a cautionary tale of waste and incompetence. ... huts and infrastructure deliberately left to rot or burned down, sensitive areas mismanaged, and allegations of intimidation or threats towards white Kiwis attempting to access the land. These are not isolated incidents - they are a pattern.

Monday, 17 November 2025

"New Zealand's unique welfare problem isn't disability or unemployment. ... It is the high rate of sole parenthood"

"New Zealand's unique welfare problem isn't disability or unemployment. ... It is the high rate of sole parenthood that sets us apart. ...

"The worst child abuse, neglect, deprivation, transience, non-preparedness for school, and later, absenteeism comes from fatherless families. These children spill through to non-achievement, gang membership, criminality and lives lost to prison and non-rehabilitation.

"Yes ... plenty of children survive. But compared to children from working, two parent families, their odds of success are heavily reduced.

"Minister for Social Development from 2008, Paula Bennett drove through some reforms. She actually got rid of the DPB. But then replaced it with the Sole Parent Payment. ... 2023 census data told us 70 percent of sole parents with dependent children receive welfare. By September 2024... there were 102,693. ...

"The number in September 2025 reached 234,000. With seasonal fluctuations the total could reach a quarter million by December."This country's propensity to put a soft-focus on hard problems is not working."~ Lindsay Mitchell from her post 'National's problem epitomised'

Wednesday, 12 November 2025

Tiri: Good Theatre, Poor History

It is good theatre. But it is a poor play. It cries out for context.

Tiri recounts what's said to be the sins of colonialism, including raupatu. But there is no confiscation in her stories.

She tells us her village was burned down. But it was she who demanded that.

And she tells us about a slaughter at Ngātapa. Which desperately needs that context.

A lot of that context involves Te Kooti, a stone killer whose spirit hovers over the whole text of the play, and the life of the protagonist

Tiri takes up Te Kooti's cause wholeheartedly, she tells us; she saw him as "my prophet." She embraced his cause just after he had burned, savaged and slaughtered 63 men, women and children at Matawhero, including Māori, "followed by the singing of Psalm 63." Several of these were prisoners whom he executed several days after the original slaughter.

Te Kooti himself was a kupapa who was later arrested for being a spy, possibly wrongly [1], and imprisoned without due process on the Chatham Islands. There, he read the Bible—mainly the Old Testament, the chapters brimming over with brutality—and formulated a new religion.

Te Kooti found in the Old Testament, with its record of the persecution of the Jews, many parallels with the plight of the Maoris. Like other Maori religious leaders who followed him, Te Kooti was regarded by his supporters as a Saviour who would lead the Maoris out of the wilderness, just as Moses had led the Jews from Egypt. Ringatu attracted a strong following in the Urewera country and the eastern Bay of Plenty.[2]

He "believed it was his God-sent function to act as the agent of divine justice for wrongs committed at that time."[3]

The slaughter at Matawhero was an example of that "justice," carried out after his escape. "A Māori survivor heard him say: 'God has told me to kill women & children, now fire on them.'"[4] (It recalls the infamous line of the Catholic shock troops slaughter of the Cathars: "Kill them all; let God sort them out.")

The campaign of revenge waged by the force of Te Kooti in the first year or two of his return not only followed the custom of utu, but was also seen as being ratified by instances recorded in the Old Testament.* As did the Hebrews, the people of the new prophet believed that their cause was a just one, and that God was behind them supporting and protecting their campaigns.

The leader of many expeditions against him, Major W.G. Mair, reported that Te Kooti relied heavily on inspiration from Jehovah, and based his decisions and movements on divine command. His actions against his enemies were justified as being brought about by their sins against the Lord, Jehovah, having cursed the people then sent Te Kooti as his agent against them to put them to the sword. According to Mair, Te Kooti 'would never spare a European nor minister of either race, as they had been the cause of all the trouble at Turanga', nor any Maori who had been 'cursed by Jehovah'. Не added that the prophet did not believe in the New Testament but was constantly quoting the Old, and could always find a passage to justify his acts or orders.

Another observer, Mr H.T. Clarke, Civil Commissioner at Tauranga, commented that Te Kooti's followers believed their leader was 'sent of God to declare His power to the world, and also to the men of sin', and were ready to carry out their leader's behests to the letter. ** Members of the Ringatu Church in the present day believe that this action was directed by God. ***

In the early engagements when they experienced great victories, this idea of divine support was strong — their successes reinforcing the belief. As time passed, however, the opposing forces grew more determined and expe-rienced, subsistence in the rough country where the party sheltered was harder, and victory became more difficult. By the fourth year of his wandering in the wilderness, when many of his people had been captured or split up and few remained, and the advantages were more often on the side of the pursuers, it must have seemed as though the biblical parallels were declining.

The prophet's withdrawal to sanctuary in the King Country might well have indicated his feeling that either his mission had been accomplished, or that the divine mandate had been withdrawn. This idea appears to be justified by Te Kooti's reported comment to his former opponent Major Keepa in 1892, that neither of them would be instrumental in bringing about unity in the country because of the blood which was upon their hands — the reason which was given in scripture for the withdrawal of blessings from the Hebrews' King David. **** [5]

Rāpata Wahawaha

Te Kooti took refuge at the naturally strong traditional pa of Ngatapa. The kupapa, reduced to 450 men by a dispute between Ngati Kahungunu and Ngati Porou, pursued him there. ...

Despite the natural strength of Ngatapa, the government forces gradually surrounded the pa, and Te Kooti seemed doomed. But, on the night of 4-5 January 1869, he and most of his people lowered themselves by ropes down a sheer cliff face and escaped into the bush. ...[6]

With Captain T. W. Porter and a contingent of Te Arawa [Wahawaha] cut Ngātapa off from its water supply. An assault on the pā on 4 January captured the outworks and the pā was abandoned during the night. In the pursuit several hundred prisoners were taken; 120 male prisoners were shot and thrown over a cliff. Rāpata, throughout his military career, executed only male prisoners taken in arms; by the standards of the time he showed restraint. Te Kooti escaped into the Urewera, and, finding new followers, [continued his raids].[7]

Wahawaha and his kupapa pursuers had their own good reasons to avenge Te Kooti's earlier slaughter. Not that this justifies this one. But it does give that much-needed context.

I was once in the Maori Land Court at Tokaanu [relates an old surveyor] when an old Maori woman, whose name I remember as Miriama, was asked her age.

"I do not know," she said, "but I was a woman grown at Te Porere." The name went through the Maoris in the courtroom like a breeze through corn. Gone was the dingy little township, the judge and the crowded courtroom, and in a flash we were away on the tussock uplands, where the mountain breeze off Tongariro is rustling the flax and scrub as McDonnell lines up his forces for the attack, and the defiant barking "hau hau" grunts of the rebels in the pa show them to be ready for the clash.

The pa was assailed on three sides at once and was soon taken. The loopholes had been made horizontal and the walls were too thick to allow the defenders to depress the muzzles of their guns; attackers easily got right up under the parapet and even stuffed up some of the loopholes with lumps of pumice. ...

Miriama had been in the pa when her husband was shot beside her. When it was seen that the day was lost, the surviving Hau Hau broke for the bush and were soon beyond reach of the Pakeha but were pursued by the "friendlies." Renata Kawepō, the middle-aged chief of the Hawkes Bay contingent — "the fat pigs of Ngatikahungunu" to quote the rebel idiom — caught up and closed with Miriama. He went with one eye missing for the rest of his days as a memento of the occasion."His followers moved forward to kill her, but he forbade them. He subsequently married her."[9]

But that was long ago, and we are back again in the grubby little courthouse in Tokaanu.

Renata's doughty opponent is standing before us, old and battered now but still full of fight.

As she warms to the stir in the court, her back straightens and her eyes flash, and her distaste with mere words as weapons in an argument becomes more apparent with every sentence. [8]

"Binney's act of homage to Ringatu people keeps faith with the present," says historian Lyndsay Head in a devastating review in the Journal of World History, "but limits her success as a historical biographer." This "quasi-historical book" is "part history, part fiction." [10]

Binney sets out to "juxtapose the different histories of Te Kooti so that each retains its integrity, purpose, and autonomy." This produces, in practice, parallel narratives that do not interact, even within their own imaginary universes. Often summary judgments substitute for discussion, as in the treatment of Te Kooti's executions.In justifying these, Binney argues that because some land belonging to Te Kooti's tribe had been confiscated, "he had been truly dispossessed of all a man could value." However, this is insufficient. Many Maori suffered the loss of land, but none took the terrible reprisals of Te Kooti and his followers. The Maori killed by Te Kooti also have descendants who retain their memories. Instead of honouring the prophet, their memories are of regret for unavenged wrong. Te Kooti's impact on non-Ringatu Maori contemporaries is not examined in this book. Nor does Binney construct a coherent personality for Te Kooti that could be used to explain his bloodier actions—although the material for such analysis seems present. [11]

While unfavourable Maori interpretations of his actions are not pursued, contemporary pakeha interpretations of the killing of their countrymen are simply dismissed. The reactions of the settlers, in whom Te Kooti awoke deeply repressed fears, are labelled repeatedly as hysteria and prejudice. [12]

Te Kooti's own attraction to and dependence on the European world constitute the central relationship on which his importance to the interpretation of New Zealand experience rests. The link between European culture and Te Kooti's politics cries out for analysis. Instead, Binney takes refuge in the biblical query, "What manner of man was this?" — an uncomfortable echo of the question asked by followers of Jesus. In a modern historical context it is mere rhetoric, and cannot supply answers to the questions of the meaning of Te Kooti's life.

Te Kooti's relationship to his own followers is described, but [nor is that] examined analytically. For example, Binney does not explain how striking visual representation of his spiritual power was constructed for his followers. This construction was a literal one, because it consisted of whare (houses), many of them jewels of Maori art, as the excellent photographs in the book attest. These houses were built on Te Kooti's command to receive him, yet his spiritual authority was often exercised in words of destruction and desolation uttered against their builders. [13]

[W]hat is the reference for the "redemption" of the title of the book? Te Kooti is said by Binney to have taught preeminently through waiata (songs, often adapted from ancient chants), but none of the unfortunately few waiata presented in this book has the redemption theme. "Redemption Songs" was previously the title of a Methodist song book, and also of a Bob Marley song. These have no apparent connection with Te Kooti (although Bob Marley is revered by some Maori now), and since no rationale is offered by Binney, the title seems irrelevant and disconcerting. [14]Irrelevant, disconcerting and—given the deserved reverence for Bob Marley—first brought to fame with his ebullient pacifist ska single 'Simmer Down'—thoroughly dishonest.

This continues through the translations on which she relies— arguments on law, land, and love "based on erroneous translations" of the waiata misrepresented in her title.

[Binney] consistently offers late twentieth-century interpretations of Maori political culture. Laying aside the erosion of meaning through mistranslation, the approach to waiata as cultural monuments has helped to hide, rather than reveal, the politics of the day. ...There are similar problems in other places, where connotations mislead rather than inform the reader. For example, chapter 5, which assembles an impressive amount of detail about Te Kooti's fighting campaigns, is titled "And Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho." There is no New Zealand parallel with the tradition of the Negro spiritual, nor between the Matawhero attack retold in the chapter and the biblical event. Binney's own narrative suggests that in 1868 Te Kooti was overwhelmingly motivated by revenge, but such a rational explanation for his actions is obscured Instead Te Kooti is provided with an implied "just cause" through his immersion in the story of the biblical Israelites. This is an example of the book's basic orientation toward the poetic and visual resonances of myth rather than historical truth. ...

Binney's lapses of judgment highlight the postmodern aspects of her attempt to speak with too many voices. [15]Belich is kinder to a colleague but more disparaging. "It is a big book in every respect," he says, "including the problematic." The task of a biographer is to explain their subject. Binney doesn't bother, her postmodern epistemology excusing her relativism and partiality.

'There can be no single truth about such a man', writes Binney, 'and this book contains many histories.' ... If this were wholly true, it would leave reviewers with the problem of which history to review, and expose Redemption Songs to serious methodological criticism. It is not wholly true. In practice as against theory. Binney usually privileges one version of history, namely her interpretation of Te Kooti's own. This interpretation, while sensitive and moderate, cannot be said to be nonpartisan — something which is perhaps most obvious in the discussion of mass killings, notably those at Poverty Bay in November 1868. [16]Mass killings are not something about which to be impartial. Ever. Binney's take however is worse than that. It's simple evasion.

1. "In 1865 most of [Te Kooti's hapu] Ngāti Maru converted to a new religion, Pai Mārire. Te Kooti and the senior chief, Tāmihana Ruatapu, were among the few who did not. At the siege of the Hauhau at Waerenga-a-hika, near Tūranga (Gisborne), from 17 to 22 November 1865, Te Kooti fought with the government forces. However, few of the government's Poverty Bay allies co-operated with any enthusiasm, while Te Kooti's elder brother Kōmene was fighting inside the pā. On 21 November Te Kooti was arrested, 'on suspicion of being a spy'. He was accused in the midst of the fighting by the old Rongowhakaata chief Pāora Parau of supplying powder to those inside the pā. But the charges could not be proved, and he was released. In March 1866 he was again arrested as a spy. ..."George Preece claimed that in February Te Kooti had sent a warning to his chief, Ānaru Mātete (younger brother of Tāmihana Ruatapu), a Hauhau leader who had gone into hiding. On 3 March Te Kooti was bundled onto the boat to Napier with the first batch of Hauhau prisoners. A song he composed on the voyage tells the people to heed the 'law of the governor' which will make good 'the work of Rura', the Pai Mārire god, who had brought all the present trouble. Despite his appeal on 4 June to McLean for a hearing of the charges against him, the next day he was sent to Wharekauri (Chatham Island) with the third batch of prisoners." ['Biography: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki,' Te Ara/NZ History]2. Sorrenson, Maori and European Since 1870, p. 43. Elsmore, Mana From Heaven, p.156

4. 'Biography: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki,' Te Ara/NZ History

5. Elsmore, Mana From Heaven, p.xxx

6. Oxford New Zealand Military History, p. 382

7. 'Biography: Wahawaha, Rāpata,' Te Ara/NZ History

8. AH Bogle, Links in the Chain: Field Surveying in New Zealand, NZ Institute of Surveyors (Wellington, 1975), p. 71.

9. Renata's Journey, p. 31

10-15. Lyndsay Head, 'Reviewed Work: Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki by Judith Binney,' Journal of World History, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 2000), pp. 136-140 (5 pages)

16. James Belich, 'Redemption Songs. A Life Of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki by Judith Binney (review),' New Zealand Journal of History, University of Auckland, Volume 30, Number 2, October 1996, pp. 182-183

Monday, 10 November 2025

Rangatiratanga means "Ownership"

IT MIGHT SURPRISE YOU to know, since so much hangs upon it, that the Treaty's term 'tino rangatiratanga' is 'a missionary neologism'—one of many. [1] Its root word is ‘rangatira,’ which was of course an original te reo word meaning ‘chief.’ This new word coined by Williams then stresses the power, authority, and agency of the chief.

Article Two of Te Tiriti promises to preserve tino rangatiratanga; courts have interpreted this in various ways to mean that chiefs (Rangatira) retain some kind of chiefly power. But Te Tiriti itself fails to fully clarify of what that power consists. [2] Lawyers since have taken full advantage of this imprecision by arguing that it means some kind of chiefly sovereignty (although not over the whole country, since each iwi only extended so far). Ned Fletcher and others have argued since that the English text agrees with this idea, saying that the sovereignty ceded by the Treaty was “compatible with ongoing tribal self-government,” suggesting then that “tino rangatiratanga” means Māori self-government.Context is important. Like most law, Te Tiriti is hierarchical. Article One focusses on sovereignty; Article Two has a focus on land and resources. There was a logical progression from one Article to another, with the first Article, logically and in law, taking precedence. Sovereignty first, then clarifying what that sovereignty is for.

So with this context then, what is chieftainship about? Answer: It is primarily about ownership — about ownership of that land and those resources. But it is ownership in a "chiefly" sense — a feudal right held by lords — analogising the neo-feudal control of a chief over a tribe's land and resources (and in some senses persons!) to that of a property right.

It is true that in translation Henry Williams has taken an approach that better aligns with the more [collectivist] Māori world-view, rather than the more individualistic European outlook. As such the Māori version does not refer to individuals holding exclusive possession of property. Instead we find chiefs exercising “chieftainship over the lands, villages and all their treasures." [4]In seeking to find a te reo word to describe the unfamiliar concept of property rights, Williams has unfortunately conflated a legitimate recognition of an individual right to property with an analogy to feudalism and a non-existent claim to a collective right. But feudalism is a busted flush. And "the expression 'collective rights' is a contradiction in terms.” [5]

This then makes for a disastrous confusion. Confusion, because the intent of Article Two is to impart property rights, an individual right. But the reference to "chieftainship" makes the promise about collective tribal rights over land with the tribes' rights embodied in a chief. Disastrous because Te Tiriti should have treated all Maori as individuals instead of as members of a tribe. But it really does nothing of the sort except by implication.

Instead, as written, it cemented in and buttressed the tribal leadership and communal structures that already existed here —encouraging the survival of this wreck of a system until morphing, as it has today, into this mongrelised sub-group of pseudo-aristocracy: of Neotribal Cronyism.

"This tribal right is clearly a right of property… To themselves they retained what they understood full well, the ‘tino Rangatiratanga,’ ‘full Chiefship,’ in respect of all their lands…’” [6]This is not trivial. This is why sovereignty, was ceded. This is what we must understand. Tino rangatiratanga ("a right of property") under kāwanatanga katoa (the "complete Government") of the British Queen.

“EVEN THE 'TINO' OF the Māori version is better understood in this context,” argues McQueen. “It does not mean that the chiefs’ authority is unqualified in a government sense. Rather it is Henry Williams’s translation of how the chiefs would retain possession of the lands, forests and fisheries. The English version emphasised such possession would continue ‘full exclusive and undisturbed.’ Williams has rendered this concept as ‘tino’ rangatiratanga. It is about Māori retaining full agency over their land and resources. It is not a statement about unqualified political sovereignty.” [Emphasis mine.]

So “rangatiratanga” relates to ownership. “Tino” gives force to this relationship, giving it the force of a property right.

NOTES:

[1] Paul Moon, The Path to the Treaty of Waitangi, David Ling Publishing, (2002) p. 147

[2] Hugh Kawharu back-translates te tino rangatiratanga as 'the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship,' which doesn't quite clarify things, although the next phrase tries, the Queen guaranteeing "to protect the Chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures ..."

In Ned Fletcher's reconstructed English text, the corresponding phrase is "full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates, Forests Fisheries and other properties ... "

[3] Ayn Rand, 'A Nation's Unity, Part II,' Ayn Rand Letter, Oct 23 1972 (New York) p. 2

[4] Ewen McQueen, One Sun in the Sky, Galatas Press (2020), p. 42-43.[5] Ayn Rand, ‘Collectivized Rights,’ in The Virtue of Selfishness, New York, Signet, June 1963

[6] William Martin, The Taranaki Question, The Melanesian Press(1860), p. 9.

RELATED:

- It's still the "chieftainship" that is the problem — NOT PC

- Kawanatanga katoa > tino rangatiratanga — A POLITICALLY INCORRECT HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND

- When was sovereignty properly established here? — A POLITICALLY INCORRECT HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND

- Ned's Puzzling Treaty — NEWSROOM

Monday, 3 November 2025

"AOTEAROA, IT IS WIDELY ASSUMED, is the original ‘indigenous name’ for New Zealand...."

|

"Some of the major King Movement meetings were held at a village called Aotearoa, some eight kilometres east of Te Kuiti. It was still known by that name at the end of the century." |

"AOTEAROA, IT IS WIDELY ASSUMED, is the original ‘indigenous name’ for New Zealand. It is certainly the ‘modern’ name favoured by many Māori and others. But our current common use and understanding of the name was probably not in existence before Western contact....

"Māori appear not to have had a name for what is now called New Zealand. The North Island was Te Ika a Maui – the fish of Maui – and the South Island Tewaipounamu, or the rivers of greenstone. The latter also had other names in legend ...

"The origins of Aotearoa are obscure. George Grey’s 'Polynesian Mythology' (1855) is sometimes credited with the first written use of the term when he recounted the legends of Maui, saying that the 'greater part of his descendants remained in Hawaiki, but a few of them came here to Aotearoa… (or in these islands).'

"But there are now long recognised problems with accepting at face value early European interpolations of tribal ‘traditions’. ... [T]here are some traditional generic notions common through much of eastern Polynesia, such as the idea that islands were hauled up from the dark depths into the light, which is where the term Aotea, or dialectical equivalent, as light may have some relevance – perhaps not so much as a specific island name, but as a place that become light. So it is possible the words Aotea, or Aotearoa, were sometimes used, but not in the sense they are commonly used today.

"For example, it is revealing that the Māori Declaration of Independence of 1835 which asserted the authority of the ‘Independent Tribes of New Zealand’ has both Māori and English versions. The Māori version of New Zealand is ‘Nu Tereni,’ a Māori pronunciation of the English name. Aotearoa is not used.

"The English version of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi has several references to the ‘Tribes of New Zealand’, ‘Chiefs of New Zealand’, ‘Natives of New Zealand’. The Māori version, it might be expected, would use the word Aotearoa, if it was in common usage. Instead it translates ‘New Zealand’ as ‘nu tirani’.

"William Williams’ Māori dictionary, first published in 1844, has no entry for Aotearoa.

"THE EARLIEST REFERENCE I have found in New Zealand’s newspapers is in the Māori language [government newspaper] 'Māori Messenger,' 1855, which mentions Aotearoa which it equated to ‘Nui Tireni.'

"So it is likely that the word Aotearoa may have had some currency, though it seems not to have been in widespread or specific use. And maybe Grey’s poetic hand [for he was Governor again at the time] is there somewhere? ...

"But the increasing usage of Aotearoa from about mid-century does have traceable origins in Māori tribal locations and politics in the colonial period, and particularly with the emergence of the Māori King Movement in the Waikato in the late 1850s, early 1860s. Some of the major King Movement meetings were held at a village called Aotearoa, some eight kilometres east of Te Kuiti – but not in more recent times? The village was also then, and is now still called Rangitoto.

"Also in the 1860s there are examples of the use of the phrase ‘the island of Aotearoa’ meaning the North Island. This usage continued throughout the century. The setting up of King Tawhio’s Great Council, or Kauhanganui, in 1892 comprised, it claimed, ‘the Kingdom of Aotearoa and the Waiponamu,’ meaning both the North and South Islands.

"It is likely that King Movement political aspirations may lie behind the claimed increasing geographic size of the region purported to be Aotearoa. But it was mostly wishful thinking in practical terms. While many Maori throughout New Zealand may have been in support of the King Movement’s general aims, most were far too independent to kowtow to its mana. At least one acerbic commentator noted Tawhiao’s nation-wide ‘constitution’ for ‘the Maori Kingdom of Aotearoa’ amounted only to ‘practically what is termed the King country.’

"THOMAS BRACKEN'S NEW ZEALAND [1870s] anthem was translated into Māori [in 1878] by T.H. Smith. New Zealand he called Aotearoa. This meaning was further entrenched with W.P. Reeves’ 1898 history of New Zealand with the title 'The Long White Cloud: Ao Tea Roa.' James Cowan’s 1907 version is entitled 'New Zealand, or Ao-te-roa (The Long Bright World).' Johannes Andersen, in the same year, published 'Māori Life in Aot-ea.'

"The now common specific ‘translation’ of Aotearoa as ‘the land of the long white cloud’ probably became more established from the 1920s or 30s.

"Both Bracken and Reeves are commonly credited with first inventing the word Aotearoa. They did not, but they helped embed the modern view among both Māori and Pākehā that Aotearoa means and is the ‘indigenous’ term for all of New Zealand. ..."~ Professor Kerry Howe, from his 2020 post 'Aotearoa: What’s in a name?' (Kerry Howe is an internationally regarded academic for his 11 books on aspects of the prehistory, history and cultures of New Zealand and the Pacific Islands)